Mark and Steve Thiessen started the morning of October 14th by conducting a search for Nelson’s Sparrows in the wetland restorations south of the Jungemann barn. No Nelson’s Sparrows were found; the highlight was counting 173 blue jays.

Photo by Monica Hall

Blue Jay

The phrase “naked as a jaybird” refers to something especially bared, and morphed from the original phrase “naked as a robin.” Blue jays are born without many feathers, naked, one might say. As the phrase morphed, so too did the preceding adjective, growing to include crazy, mean, and saucy as a jaybird. The slight is obvious in calling someone “crazy as a jaybird,” but the slight to the blue jay might be overlooked. With a reputation that precedes them, blue jays are often scorned by birders who call them thugs and overly aggressive at feeders.

Blue jays at feeder, photo by Jo Zimny Photos

Indeed, blue jays have been found to ransack the nests of other songbirds. At feeders, jays have been known to mimic the call of red-shouldered hawks, perhaps to scare other songbirds into thinking a raptor is near. They'll steal feed from squirrels, nuthatches, and woodpeckers, but it is a rather uncommon occurrence.

Blue jays are opportunistic. A majority of their diet consists of acorns, nuts, seeds, grains, and fruits. Insects become an important part of their diet during the breeding season. However, the birds do eat a broad diet including frogs, toads, bird eggs, nestlings, and rarely roadkill or deceased animals.

These birds belong to the corvid family, and accordingly are incredibly smart. Researchers trapping and marking blue jays have difficulty catching the same bird twice. Captive jays have used instruments to pull food from outside a cage to within it. Some blue jays have remarkably learned to pluck ants from a hill, wiping the formic acid of the ants onto their breasts and making the ants digestible. Additionally, blue jays will cache anywhere from 3,000-5,000 acorns each year—relocating a good majority of those acorns.

Oak savanna, photo by Joshua Mayer

Hugely important to the ecosystems of oak savannas and oak woodlands, blue jays have been considered a keystone species for the role they play in dispersing the acorns of oak trees. If each bird “forgets” 5% of its crop, then an oak savanna will nevertheless have thousands of germinating oaks each year. Another mark of genius for blue jays is that they've been shown to discern fertile acorns with 88% accuracy. Other acorns may be infested with fungus, rust, or the acorn weevil, which lays eggs inside the growing acorn that will feed its larvae, which will eventually use long snouts to burrow a hole out of the acorn.

Photo by Stan Lupo

While oak trees arguably have their own role as a keystone species—allowing sunshine into the understory, fueling fire with combustible leaves, and providing food (acorns) for 150 species of birds and mammals—blue jays are bolted to that same role. Jays allow oak dispersal to an astounding level, as the birds will carry acorns over 2.5 miles away from the source tree. In fact, after the last ice age, oak species dispersed into glacier-torn areas faster than wind dispersed seeds. It is thought that this is due to the dispersing behavior of blue jays.

“What about squirrels?” you might be asking. Squirrels also play an important role, but their dispersal is not as impressive as a blue jay's. The cached acorns of squirrels are most likely to be found within feet of the source tree. However, squirrels play a dynamic role in shaping the composition of the forest or savanna trees. Squirrels prefer to cache red and black oak nuts, while they prefer to eat white and bur oak nuts. This is because the red and black oak nuts are loaded with tannins, and store better for long periods. White oak acorns germinate in the fall and therefore don't keep as well as the red oak acorns. With fewer tannins, squirrels consume white oak treats immediately, and don't cache as many acorns from those white oak species. Even when white oaks are cached, the embryo is often excised.

Thus, blue jays may help to spread white and bur oak trees since they pick out fertile acorns and often find suitable sites for these acorns while burying them with a small amount of substrate. One study found that blue jays cached 55% of the acorns in a given area, while eating another 20% while they were gathering. Another interesting adaption from the blue jay is its ability to move multiple acorns per trip. The bird accomplishes this by storing some acorns in its “gular pouch” which can hold 2-3 acorns, stroring one or two in its mouth, and storing one on the tip of its beak.

Photo by Monica Hall

Blue jays live monogamous lives and run complex social circles throughout the year. It is thought that some birds recognize each other based on the markings of the face. Jays can be found in most forested habitats throughout Wisconsin, especially somewhere with oak trees. Here at Faville Grove, you can find these fascinating birds throughout the sanctuary, but they've been especially abundant in the ledge savanna where they've been plucking acorns.

Written by Drew Harry, Faville Grove Sanctuary land steward

Crows, and Blue Jays, and West Nile, oh my

For some people, American crows and blue jays are considered the bullies of the avian world. In Wisconsin, a hunting season on crows was established to deal with their overpopulation in urban areas where they and their noisy blue jay buddies cause problems. But a friend who lives in Illinois shared that he has noticed that crow population has greatly declined, and he wondered what was causing it.

Could this decline in corvid numbers be caused by the West Nile virus (WNV), a disease that has been a factor in the decline of birds for some time? We looked at population trends of these two species by examining data from our citizen science project, the Poynette Christmas Bird Count, to learn a little more about WNV and the impacts on crows and blue jays in the area. We also looked at recent statistics of the Center for Disease Control (CDC), recent articles written on the subject, and the work of other agencies that are associated with WNV.

Photo by Eric Begin

The CDC states that “West Nile virus has been detected in a variety of bird species. Some infected birds, especially crows and jays, are known to get sick and die from the infection.” The DNR also follows this virus and its effect on wildlife, and the USGS Wildlife Health Center in Madison has been studying this virus for decades in an attempt to find a way counter WNV.

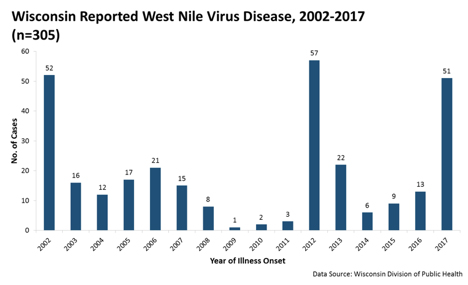

The Wisconsin Division of Public Health states “WNV is an arbovirus that is transmitted by a bite of an infected mosquito. West Nile virus (WNV), which has been widespread in Africa, southern Europe, the Middle East and western Asia, first appeared in the New York City area of the United States in 1999. The first human cases of WNV in Wisconsin appeared in 2002. Few mosquitoes actually carry the virus.”

In nature, mosquitoes become infected by feeding on infected birds and can transmit the virus to other animals, birds, and humans. The Wisconsin Division of Public Health monitors dead birds for WNV as an early warning system to indicate that the virus may be present in an area. “This information is important to heighten awareness in the prevention and control of WNV disease.”

The number of dead bird cases per year where WNV was the cause of mortality.

From 2004 Laura Erickson’s For the Birds Radio Program: West Nile Virus: Crows dealing with grief

“Now that it’s October, West Nile Virus is once again rearing its ugly head. Since the disease first appeared in America in 1999, 625 people have died from the disease. So far this year, the human death toll is 59, including 2 in Minnesota and 1 in Wisconsin.

As bad as West Nile Virus is for humans, it’s even worse for birds. Most of us have probably already been exposed to the virus and developed immunity. Fewer than 5% of people who are infected with the virus get sick at all, and of them, most get only minor flu symptoms. The people most vulnerable are those with immune system deficiencies, and so it’s very important to protect ourselves and especially the very old and the very young and people who’ve been sick from mosquito bites. We can go to a store and buy repellants, and we live in houses that can be fairly effectively closed off from insects.

Birds are helpless to defend themselves against biting insects, and are far more vulnerable to this disease than we are. 99 – 100% of all crows exposed to the virus not only get sick—they die. Great Horned Owls, Red-tailed Hawks, Blue Jays, and chickadees are other species that are extremely susceptible to the disease.

A crow in flight, photo by Arlene Koziol

American Crow counts fell to a 15-year low in the Midwest on Christmas Bird Counts for 2002-2003, and in Ithaca, New York, where the disease first appeared in 1999, the crow population has been decimated. That particular local crow population has been under close scrutiny since 1988 by Kevin McGowan of the Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology and his students, who have marked as many as a thousand individual crows and keep track of each bird as an individual. Crows are extraordinarily intelligent and sociable, and family units remain together for a long time, with young birds typically helping their parents raise new broods for a few years before they find a mate and start their own families. But in 2002, fully a third of McGowan’s study birds were found dead from West Nile Virus, and last year another third died. McGowan likens the impact on crows to the effect the Black Death had on humans. Crows don’t abandon their family members as they die—McGowan says that at least one crow always remains with a dying bird. In one family unit of 8 birds, all but 2 have died from the disease, and the surviving females have joined other family units and help them raise their babies. Orphaned fledgling crows have been adopted by other crows. Widowed adults are moving back in with their parents. Crows apparently can’t live alone, and even pairs won’t nest without a whole group, which will slow the speed at which the survivors will repopulate the area. Many people don’t like crows, the most human-like of all birds with their complex language and social behaviors and intelligence. But our measure as human beings is related to how much compassion we have for all the creatures on this little planet.”

Average number of individual crow and blue jays counted during the Poynette Christmas Bird County

These tables provide us with rough ideas of American crow and blue jay numbers for our area in late December for the past 39 years of the Poynette Christmas Bird Count.

One can see that there is a lot of difference between highs and lows with the number of dead birds reported to the health Department and also in Poynette CBC data. Crows fluctuated between 215 to 1,293 while blue jay numbers fluctuated between 123 and 586. It is impressive in the past 39 years that our Christmas bird counters tallied 29,300 crows and 12,700 blue jays. Overall, without a lot of statistical data, it appears that our crow and blue jay populations have not been greatly impacted by WNV.

Photo by Kelly Colgan Azar

A crow calling in the distance was the first bird heard this morning from the house. The first report on the breeding bird atlas this week was a crow carrying nesting materials. We are ready for spring to resume the work of the breeding bird atlas by recording species of crows and blue jays. We wonder if warming temperatures that accompany climate change affect mosquito populations and result in an increase of WNV.

Thanks to Laura Erickson who spoke at the 50th anniversary celebration for Goose Pond Sanctuary for her information on crows and WNV.

Written by Mark Martin and Sue Foote-Martin, Goose Pond Sanctuary resident managers, and Graham Steinhauer, Goose Pond Sanctuary land steward

Blue Jay

The phrase “naked as a jaybird” refers to something especially bared, and morphed from the original phrase “naked as a robin.” Blue jays are born without many feathers, naked, one might say. As the phrase morphed, so too did the preceding adjective, growing to include crazy, mean, and saucy as a jaybird. The slight is obvious in calling someone “crazy as a jaybird,” but the slight to the blue jay might be overlooked. With a reputation that precedes them, blue jays are often scorned by birders who call them thugs and overly aggressive at feeders.

Photo by Eric Begin

Indeed, blue jays have been found to ransack the nests of other songbirds. At feeders, jays have been known to mimic the call of red-shouldered hawks, perhaps to scare other songbirds into thinking a raptor is near. They'll steal feed from squirrels, nuthatches, and woodpeckers, but it is a rather uncommon occurrence.

Blue jays are opportunistic. A majority of their diet consists of acorns, nuts, seeds, grains, and fruits. Insects become an important part of their diet during the breeding season. However, the birds do eat a broad diet including frogs, toads, bird eggs, nestlings, and rarely roadkill or deceased animals.

These birds belong to the corvid family, and accordingly are incredibly smart. Researchers trapping and marking blue jays have difficulty catching the same bird twice. Captive jays have used instruments to pull food from outside a cage to within it. Some blue jays have remarkably learned to pluck ants from a hill, wiping the formic acid of the ants onto their breasts and making the ants digestible. Additionally, blue jays will cache anywhere from 3,000-5,000 acorns each year—relocating a good majority of those acorns.

Photo by Joshua Mayer

Hugely important to the ecosystems of oak savannas and oak woodlands, blue jays have been considered a keystone species for the role they play in dispersing the acorns of oak trees. If each bird “forgets” 5% of its crop, then an oak savanna will nevertheless have thousands of germinating oaks each year. Another mark of genius for blue jays is that they've been shown to discern fertile acorns with 88% accuracy. Other acorns may be infested with fungus, rust, or the acorn weevil, which lays eggs inside the growing acorn that will feed its larvae, which will eventually use long snouts to burrow a hole out of the acorn.

Photo by Robert Nunnally

While oak trees arguably have their own role as a keystone species—allowing sunshine into the understory, fueling fire with combustible leaves, and providing food (acorns) for 150 species of birds and mammals—blue jays are bolted to that same role. Jays allow oak dispersal to an astounding level, as the birds will carry acorns over 2.5 miles away from the source tree. In fact, after the last ice age, oak species dispersed into glacier-torn areas faster than wind dispersed seeds. It is thought that this is due to the dispersing behavior of blue jays.

“What about squirrels?” you might be asking. Squirrels also play an important role, but their dispersal is not as impressive as a blue jay's. The cached acorns of squirrels are most likely to be found within feet of the source tree. However, squirrels play a dynamic role in shaping the composition of the forest or savanna trees. Squirrels prefer to cache red and black oak nuts, while they prefer to eat white and bur oak nuts. This is because the red and black oak nuts are loaded with tannins, and store better for long periods. White oak acorns germinate in the fall and therefore don't keep as well as the red oak acorns. With fewer tannins, squirrels consume white oak treats immediately, and don't cache as many acorns from those white oak species. Even when white oaks are cached, the embryo is often excised.

Photo by Don Miller

Thus, blue jays may help to spread white and bur oak trees since they pick out fertile acorns and often find suitable sites for these acorns while burying them with a small amount of substrate. One study found that blue jays cached 55% of the acorns in a given area, while eating another 20% while they were gathering. Another interesting adaption from the blue jay is its ability to move multiple acorns per trip. The bird accomplishes this by storing some acorns in its “gular pouch” which can hold 2-3 acorns, storing one or two in its mouth, and storing one on the tip of its beak.

Blue jays live monogamous lives and run complex social circles throughout the year. It is thought that some birds recognize each other based on the markings of the face. Jays can be found in most forested habitats throughout Wisconsin, especially somewhere with oak trees. Here at Faville Grove, you can find these fascinating birds throughout the sanctuary, but they've been especially abundant in the ledge savanna where you’ll find them plucking acorns.

Written by Drew Harry, Faville Grove Sanctuary land steward

Cover photo by Eric Bégin FCC